Cell Transport Study Guide: An Overview

Cellular transport‚ crucial for life‚ involves moving substances across membranes using passive and active mechanisms‚ powered by gradients or ATP.

Understanding these processes – diffusion‚ osmosis‚ and active transport – is fundamental to comprehending cell function and physiological processes.

Cell membrane transport is a vital process for all living cells‚ governing the movement of substances between the intracellular and extracellular environments. This dynamic exchange is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis‚ nutrient uptake‚ waste removal‚ and signaling. Transport mechanisms are broadly categorized as passive‚ requiring no cellular energy expenditure‚ and active‚ which necessitates energy input‚ typically in the form of ATP.

The selective permeability of the cell membrane‚ dictated by its phospholipid bilayer structure and embedded proteins‚ plays a critical role in regulating transport. Passive transport relies on concentration gradients‚ moving substances down their gradient via simple diffusion or facilitated diffusion with the aid of transport proteins. Conversely‚ active transport overcomes concentration gradients‚ utilizing energy to move substances against their gradient‚ crucial for establishing and maintaining cellular gradients like the sodium-potassium gradient.

The Cell Membrane: Structure and Function

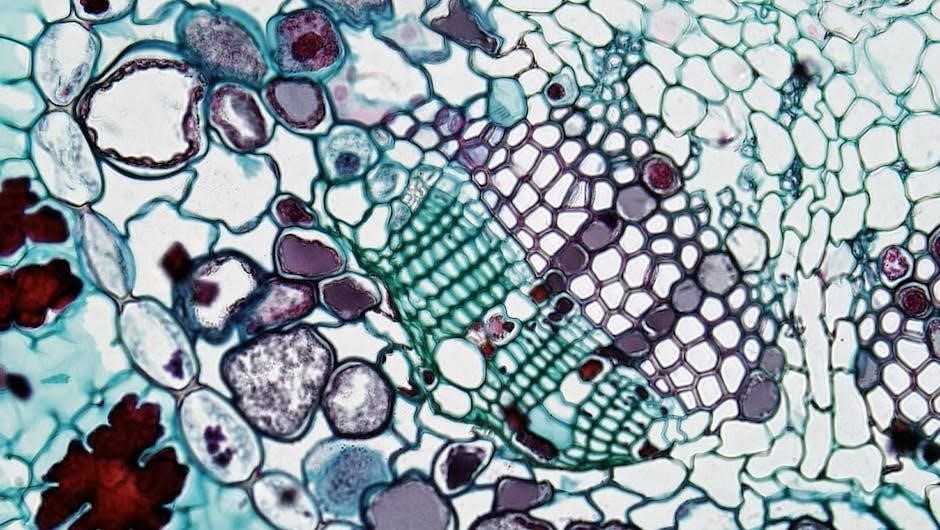

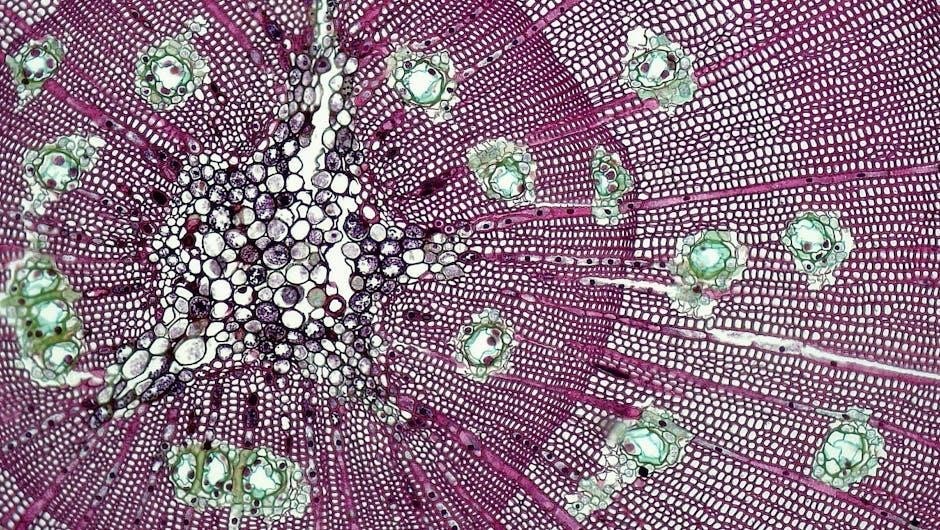

The cell membrane‚ a biological barrier‚ is primarily composed of a phospholipid bilayer‚ providing a flexible structure with hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions. Embedded within this bilayer are proteins – integral and peripheral – that perform diverse functions‚ including transport‚ enzymatic activity‚ and cell signaling. Cholesterol molecules also contribute to membrane fluidity and stability.

This structure dictates the membrane’s selective permeability‚ controlling which substances can freely pass through and which require assistance. The membrane isn’t merely a passive barrier; it actively participates in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Transport proteins‚ forming channels or carriers‚ facilitate the movement of specific molecules across the membrane. The membrane’s fluidity allows for dynamic rearrangements‚ essential for processes like endocytosis and exocytosis‚ further highlighting its crucial role in cellular transport.

Passive Transport Mechanisms

Passive transport relies on concentration gradients‚ requiring no cellular energy expenditure. Diffusion‚ facilitated diffusion‚ and osmosis are key processes enabling substance movement.

Simple Diffusion: Movement Down the Concentration Gradient

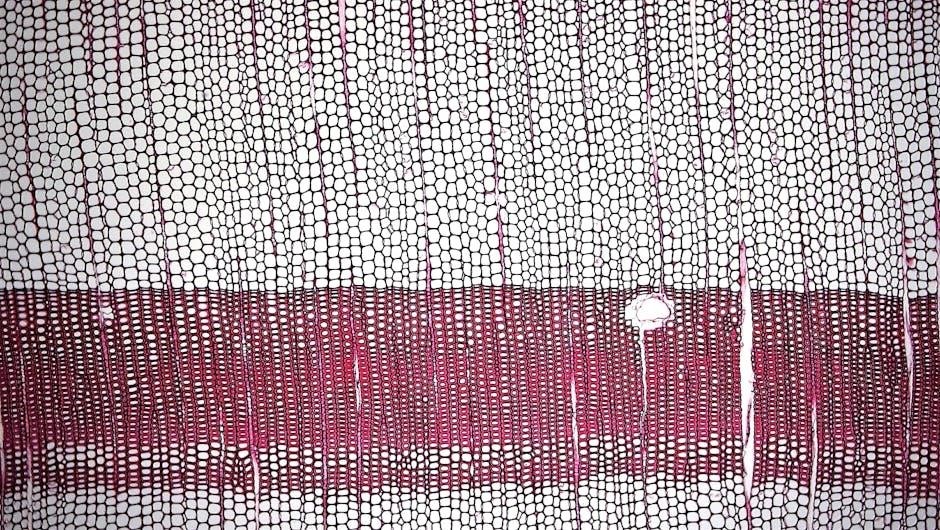

Simple diffusion is a passive transport mechanism where substances move across the cell membrane from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration‚ following the concentration gradient. This movement doesn’t require the assistance of membrane proteins; molecules simply pass through the lipid bilayer.

The rate of diffusion is influenced by factors like temperature‚ the size of the molecule‚ and the membrane’s permeability. Smaller‚ nonpolar molecules‚ such as oxygen and carbon dioxide‚ diffuse more readily than larger‚ polar molecules. Essentially‚ the cell allows sodium ions to passively diffuse into the cell when a channel opens‚ driven by the existing concentration gradient.

This process continues until equilibrium is reached‚ meaning the concentration is equal on both sides of the membrane. It’s a fundamental way cells obtain necessary molecules and eliminate waste products without expending energy.

Facilitated Diffusion: Protein-Assisted Transport

Facilitated diffusion is another form of passive transport‚ but unlike simple diffusion‚ it requires the assistance of membrane proteins to move substances across the cell membrane; These proteins‚ either channel or carrier proteins‚ provide a pathway for molecules that cannot easily cross the lipid bilayer on their own.

Channel proteins create a pore through the membrane‚ allowing specific ions or small polar molecules to pass through. Carrier proteins bind to the substance and undergo a conformational change to transport it across. Both types follow the concentration gradient‚ requiring no energy input.

This process is crucial for transporting larger molecules like glucose and amino acids. While it relies on proteins‚ it’s still passive because it doesn’t expend cellular energy; it simply facilitates movement down the concentration gradient.

Osmosis: Water Movement Across Membranes

Osmosis is a specialized type of passive transport focused specifically on the movement of water across a semi-permeable membrane. This movement occurs from an area of high water concentration to an area of low water concentration‚ aiming to equalize the solute concentration on both sides.

Water potential‚ influenced by solute concentration and pressure‚ drives this process. Water moves to regions with lower water potential. The cell membrane‚ while permeable to water‚ restricts the passage of many solutes‚ creating the necessary concentration gradient.

Osmosis is vital for maintaining cell turgor pressure in plants and ensuring proper cell volume in animals. Understanding osmotic pressure is crucial‚ as imbalances can lead to cell swelling or shrinking‚ impacting cellular function and potentially causing damage.

Active Transport Mechanisms

Active transport requires energy‚ typically ATP‚ to move substances against their concentration gradients. This process is essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis and function.

Primary Active Transport: Utilizing ATP Directly

Primary active transport directly utilizes the energy derived from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) hydrolysis to fuel the movement of molecules across the cell membrane‚ opposing their concentration gradients. This fundamental process is critical for establishing and maintaining ionic imbalances essential for various cellular functions.

Unlike passive transport‚ which relies on diffusion‚ primary active transport necessitates an energy input. The energy released from ATP breakdown directly powers the conformational changes in transport proteins‚ enabling them to bind to and translocate specific ions or molecules. These proteins‚ often called pumps‚ actively ‘push’ substances against their natural flow.

A prime example is the sodium-potassium pump‚ a vital component of animal cell membranes. It expends ATP to transport sodium ions out of the cell and potassium ions into the cell‚ maintaining electrochemical gradients crucial for nerve impulse transmission and cellular volume regulation. Without this direct ATP utilization‚ these gradients would dissipate‚ disrupting essential cellular processes.

Secondary Active Transport: Harnessing Ion Gradients

Secondary active transport leverages the electrochemical gradients established by primary active transport to move other substances across the cell membrane. It doesn’t directly utilize ATP; instead‚ it ‘harnesses’ the potential energy stored in the ion gradients created by pumps like the sodium-potassium pump.

This transport mechanism relies on the simultaneous movement of two substances. One substance moves down its concentration gradient‚ providing the energy needed to move another substance against its gradient. This coupling allows cells to transport molecules they otherwise couldn’t move efficiently.

There are two main types: symport‚ where both substances move in the same direction‚ and antiport‚ where they move in opposite directions. For example‚ sodium ions flowing down their gradient can drive the uptake of glucose into cells‚ even against its concentration gradient. This efficient system demonstrates how cells capitalize on pre-existing gradients for transport.

The Sodium-Potassium Pump: A Key Player in Cellular Transport

The sodium-potassium pump (Na+/K+ ATPase) is a quintessential example of primary active transport‚ critically maintaining cellular ion gradients. This integral membrane protein utilizes ATP hydrolysis to move sodium ions (Na+) out of the cell and potassium ions (K+) into the cell‚ both against their respective concentration gradients.

This process isn’t merely about ion balance; it’s fundamental for numerous cellular functions. It establishes the resting membrane potential essential for nerve impulse transmission‚ drives secondary active transport‚ and regulates cell volume. For every ATP molecule hydrolyzed‚ three sodium ions are pumped out‚ and two potassium ions are pumped in.

The pump’s activity is crucial for excitable cells like neurons and muscle cells‚ but it’s present in nearly all animal cells. By creating and maintaining these ion gradients‚ the sodium-potassium pump is a cornerstone of cellular physiology.

Transport of Large Molecules

Large molecules cross membranes via vesicular transport – endocytosis (into the cell) and exocytosis (out of the cell) – utilizing energy and membrane remodeling.

Endocytosis: Bringing Substances Into the Cell

Endocytosis is an active transport mechanism where substances are brought into the cell by engulfing them within the cell membrane‚ forming vesicles. This process requires energy expenditure‚ as it works against the concentration gradient. There are several types of endocytosis‚ each with a specific mechanism.

Phagocytosis‚ often termed “cellular eating‚” involves the cell engulfing large particles‚ such as bacteria or cellular debris. The cell membrane extends around the particle‚ forming a large vesicle called a phagosome. This is a crucial process for immune cells.

Pinocytosis‚ or “cellular drinking‚” involves the uptake of extracellular fluid containing dissolved solutes. The cell membrane invaginates‚ forming small vesicles containing the fluid. It’s a non-specific process‚ taking in whatever is present in the surrounding fluid. Both phagocytosis and pinocytosis are vital for nutrient acquisition and waste removal.

Exocytosis: Releasing Substances From the Cell

Exocytosis is essentially the reverse of endocytosis – an active transport process where substances are exported from the cell. Vesicles containing these substances‚ formed within the cell (often by the Golgi apparatus)‚ migrate to the cell membrane.

These vesicles then fuse with the plasma membrane‚ releasing their contents outside the cell. This process requires energy‚ typically in the form of ATP‚ to facilitate the membrane fusion. Exocytosis is crucial for various cellular functions‚ including neurotransmitter release‚ hormone secretion‚ and waste removal.

Essentially‚ it’s how cells communicate with their environment and maintain cellular homeostasis. The released molecules can then signal other cells or contribute to the extracellular matrix. This process is highly regulated and essential for proper cellular function and organismal health.

Phagocytosis: Cellular Eating

Phagocytosis‚ literally “cell eating‚” is a specialized form of endocytosis where the cell engulfs large particles‚ such as bacteria‚ cellular debris‚ or even entire cells. This process is primarily carried out by phagocytes – specialized immune cells like macrophages and neutrophils – but can occur in other cell types as well.

During phagocytosis‚ the cell membrane extends outwards‚ forming pseudopods (“false feet”) that surround the target particle. These pseudopods eventually fuse‚ enclosing the particle within a vesicle called a phagosome. The phagosome then fuses with a lysosome‚ an organelle containing digestive enzymes.

These enzymes break down the engulfed material‚ and the resulting molecules are either used by the cell or expelled as waste. Phagocytosis is a critical defense mechanism against pathogens and plays a vital role in tissue remodeling and immune responses.

Pinocytosis: Cellular Drinking

Pinocytosis‚ often termed “cell drinking‚” is another type of endocytosis‚ but unlike phagocytosis‚ it involves the uptake of extracellular fluid containing dissolved solutes. This is a non-specific process‚ meaning the cell doesn’t selectively target specific molecules; instead‚ it samples the surrounding fluid.

The cell membrane invaginates‚ forming small vesicles that pinch off and enter the cytoplasm. These vesicles‚ called pinocytic vesicles‚ contain a small volume of extracellular fluid and any dissolved substances present. Pinocytosis is a continuous process‚ constantly replenishing the cell’s fluid and nutrient supply.

It’s crucial for various cellular functions‚ including nutrient absorption and maintaining cellular hydration. While less selective than receptor-mediated endocytosis‚ pinocytosis contributes significantly to the cell’s overall intake of essential molecules;

Factors Affecting Transport Rates

Transport rates are influenced by concentration gradients‚ temperature‚ membrane surface area‚ and permeability—all impacting how quickly substances cross the cell membrane.

Concentration Gradients and Temperature

Concentration gradients are primary drivers of passive transport‚ dictating the movement of substances from areas of high to low concentration. The steeper the gradient‚ the faster the diffusion rate‚ as molecules naturally disperse to achieve equilibrium. This principle applies to both simple and facilitated diffusion‚ influencing the influx of sodium ions through passive channels‚ as highlighted in membrane transport studies.

Temperature significantly impacts kinetic energy‚ directly affecting molecular motion. Higher temperatures accelerate molecular movement‚ thus increasing diffusion rates. Conversely‚ lower temperatures slow down molecular motion‚ reducing transport speed. However‚ extremely high temperatures can denature proteins involved in transport‚ disrupting facilitated diffusion and active transport mechanisms. Therefore‚ optimal temperatures are crucial for maintaining efficient cellular transport processes‚ ensuring proper physiological function.

Membrane Surface Area and Permeability

Membrane surface area directly correlates with the rate of transport; a larger surface area allows for more transport proteins and greater diffusion capacity. Cells adapted for high transport rates‚ like intestinal cells with microvilli‚ exemplify this principle. Increasing the surface area maximizes the opportunities for molecules to cross the membrane efficiently.

Permeability‚ determined by the membrane’s composition and the characteristics of the transported substance‚ dictates how easily molecules pass through. Lipid solubility‚ molecular size‚ and charge influence permeability. Membranes with higher permeability facilitate faster transport. Active transport mechanisms can alter permeability by creating concentration gradients‚ as seen with the sodium-potassium pump‚ powering sodium ion transport. Understanding both surface area and permeability is vital for comprehending overall transport efficiency.

Clinical Relevance of Cell Transport

Cell transport dysfunction underlies numerous clinical conditions. Cystic fibrosis‚ for instance‚ results from a defective chloride channel‚ disrupting ion balance and mucus production. Diabetes impacts glucose transport via insulin-dependent transporters‚ leading to hyperglycemia. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for targeted therapies.

Active transport failures can cause imbalances in ion concentrations‚ affecting nerve and muscle function. The sodium-potassium pump’s role in maintaining cellular volume means its disruption can lead to swelling or shrinking. Furthermore‚ cancer cells often exhibit altered transport properties‚ impacting drug delivery and resistance. Investigating cell transport provides insights into disease pathogenesis and potential therapeutic interventions‚ highlighting its clinical significance.